Judging Routt County

04/01/2012 01:00AM ● By Walt Daub

Routt County Courthouse as it stands today. Photo by Deborah Olsen.

by Walt Daub

Historic Courthouse in the Heart of Old Town

Steamboat Springs native Bob Wither, who died in 2001, used to tell the story of the day in the early 1920s that he went wandering behind the county courthouse. He was admiring this new architectural marvel.

His reverie was broken by a familiar voice: “Hey, kid! Hey, Wither kid!” It was the sheriff in distress, having locked himself in the courthouse jail. Most likely, he’d locked himself in the “bear cage” – the jail cell that was relocated from the former county seat in Hahn’s Peak. Having served as the county jail from 1879 to 1912, this was also the infamous cage from which Harry Tracy, a member of Butch Cassidy’s Wild Bunch gang, escaped in 1898.

Wither’s story is one of many that shape the living character of the historic Routt County courthouse. It’s an architectural gem in the heart of downtown Steamboat. It’s also the local site of an unprecedented number of quirky stories, legal battles, community banter, marriage and divorce, divided politics, epic collaborations and agonizing local decisions.

Shaping justice

Ultimately the people who flowed through Routt County’s courthouse gave it its character. Local historian and Steamboat native Jim Stanko tells of bootlegging, kidnapping and murder trials that happened there. He recalls his weekly Boy Scout meetings there in the 1950s, and later, meetings held by both political parties, including their respective local caucuses.

For decades, the courthouse was the practical heart and social center of the community, Stanko says. Each week during the winter, eight or nine country schools came to the courthouse to join in a spelling bee, and Stanko remembers his Southside schoolhouse making a field trip there every spring. He reminisces about the sheriff locking young visiting students in the jail, just for the experience.

There was a time, Stanko adds, when low-numbered Routt County license plates were so highly valued that a line of hopefuls would weave out the front door the day they became available.

Local historian George Tolles recalls decades of political and committee meetings at the courthouse. Almost everything that happened there in the late 1900s had a civic element, he recalls, from paying taxes, licensing, auto and voter registration, to a broad variety of community activities. Even the trials had a community flavor, he recalls, the hallway during recess like a bus station with lawyers, clients, jurors, observers and friends. Whatever the occasion, the building offered a strong, comforting sense of community, Tolles recalls.

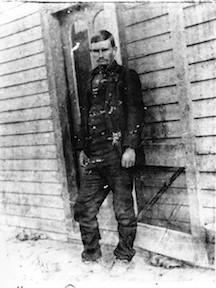

Harry Tracy, a member of Butch Cassidy's Wild Bunch gang, who escaped from the old jail. Photo courtesy of Tread of Pioneers Museum.

Finding its place

Steamboat’s first courthouse was located in a two-story structure known as the J. W. Hugus & Co. building on Lincoln Avenue, between Ninth and 10th streets. Today, it’s called the Lorenz Building. The county leased the space for three years before purchasing it for $7,000 in 1915. The county clerk, treasurer and jail shared the ground floor. The courtroom was upstairs.

In 1920, anticipating the construction of a new courthouse, Routt County’s commissioners purchased land on Lincoln Avenue between Fifth and Sixth streets for $10,500. They hired Robert Kenneth Fuller of Denver to design the facility.

Of course, controversy ensued. Not unlike the raging debate at the turn of this century over the judicial center that now resides west of downtown, in 1920 some folks recognized an overwhelming practical necessity for a new courthouse and others opposed it on the grounds of any new tax expenditure.

On Oct. 22, 1920, the “Routt County Sentinel” headline read, “All County Records Now in Danger of Destruction.” In the subsequent article, County Judge Charles A. Morning addressed the construction financing debate and a dire need to preserve county records – including the only official record of the region’s water rights.

“There is a considerable lack of information,” Morning stated. Responding to one vociferous citizen, he said, “Just the other day I heard a man ‘kick’ about the bond proposition because it would so greatly increase his taxes.” Confirming the valuation of the gentleman’s property at $820, Morning reported that for that particular citizen, the bond would result in “the horrible imposition” of 16 cents a year in increased taxes.

A courthouse financing proposition went to the voters, and bond authorization passed narrowly – 806 in favor and 733 against. Ultimately, Morning’s concerns were prescient. The A & G Mercantile building,the second floor of which had served as the courthouse annex since the late 1920s, burned to the ground in spring 1961.

Getting it off the ground

While studying historic building preservation, local designer Ellen Ladley delved deep into the architectural underpinnings of Routt County’s courthouse. “Why was it designed the way it was designed, such a long time ago?” she wondered. “In the 1920s there was not a lot of formal-looking design in Steamboat. We were still mining. In fact, there was not a lot of anything. You can find a picture of it in almost every book on Steamboat. It seems to be the largest building standing….It seems odd compared to the red brick and log structures surrounding it….almost too formal.”

Routt County’s courthouse was built to impress. It was an enormous leap from the dirt floor and sod roof structure that Hayden commissioned Albert H. Smart to build for $100 when that town was the county seat in 1877. The new courthouse cost $122,000 and took more than a year to build.

“Our historic courthouse followed a similar evolution to the story of the ‘Three Little Pigs.’ First, it was sticks and stones with a dirt roof and floor, then we moved on to a solid wood structure in the middle of nowhere; evolving to a brick structure on a main street; and, finally graduating to the solid stone structure of permanence it is today – something to last forever,” Ladley explains.

Soon after the bond passed, Fuller presented his design for a 6,844-square-foot, three-story courthouse. He set it 80 feet back from Lincoln Avenue, with a gracious front lawn. It reflects a simplified Renaissance revival façade with beaux arts influences, built of steel and reinforced concrete – fireproof throughout.

While the design reflects sophisticated turn-of-the-20th century sensibilities, much of the material is local, or at least from Colorado. Rough sandstone was quarried from Emerald Mountain to create the building’s rusticated base – a strong textural element that gives the building visual weight and contrasts with the smoothly finished, squared block surfaces above.

The façade’s blond bricks came from Golden and were laid in a symmetrical design with squared pilasters that delineate the building into nine vertical bays transected by two horizontal terra cotta rings that clearly mark the individual floors. Terra cotta adds the classical details, including the tapered cornice, a series of decorative cartouche and garland friezes.

The masonry walls are 18 inches thick. Large open spaces allow good air circulation to conserve heat and tall windows bring in natural light. The flat roof was engineered for Routt County’s 300-plus-inch snow loads. Hallways are finished in terrazzo. The first floor was designed as the sheriff’s office, including accommodations for 50 inmates, with separate sections for juveniles and women. The original courthouse floor plan also included the latest design to prevent jail breaks – a far cry from the “bear cage.” Set a few feet below ground level, the first floor provided three large storage vaults for county records. A vault door from the old Hahn’s Peak county building provides entrance to one of the main repositories to this day.

The main floor accommodated county officials and the third floor housed a 200-square-foot county courtroom and a 2,400-square-foot district courtroom, two judges’ chambers, a jury suite with overnight lodgings for men and women jurors, a witness waiting room, an attorney consulting room and public restrooms. A pamphlet distributed at the building’s dedication ceremony in December 1923 proclaims the District Court chamber as “the most beautiful room in Northwestern Colorado.”

Arched ceilings represent Beaux Arts architectural style. Photo courtesy of Tread of Pioneers Museum.

A grand opening

The courthouse is a typical Beaux Arts architectural style. Two 1.5-story Doric columns flank the front door. Above the main double oak doors “Routt County” is clearly engraved. Inside, four steps lead up from street level with a Roman-arched transom embellished by a band of art deco geometric diamonds.

“It exemplifies the height of the eclectic classical architectural movement in the United States,” says Tom Davis of Kelly and Stone Architects.

In September 1922, the cornerstone was laid with a sealed copper box of memorabilia that is scheduled to be opened in 2023. The treasures include a 1921 linen map of Routt County, a 1922 Victory silver dollar, editions of Steamboat and Denver newspapers, lists of county and school officials, rosters from local organizations and a signed statement from Steamboat founders James and Margaret Crawford concerning the building’s site.

John D. Crawford, son of Steamboat’s founder, was the county clerk and recorder at the time. (He was the longest-serving clerk in the state of Colorado when he retired in 1944.) The cornerstone celebration was a grand affair with Grand Marshall A.C. Moulton presiding and Judge Morning as the grand orator. More than 60 local Masons, who took great pride in all phases of the stone and brick construction, proudly marched to the courthouse grounds in a parade.

Today, there aren’t many visible changes to the historic building. It’s still home to the Routt County commissioners’ and district judicial offices. Financing from the State Historic Fund helped complete renovations in 2008. The old district courtroom kept its historic look and feel as it morphed into the county commissioners’ hearing room. The county courtroom was remodeled as a conference room and kitchen area. The whole structure got green upgrades to conserve energy, a new roof and window rehabilitation.

“I imagine this courthouse will be standing for years to come, and will age like fine buildings of its kind in European nations. Right here in the middle of Steamboat,” Ladley says.