Mountainside

12/01/2008 01:00AM ● By Eugene Buchanan

Holiday 2008:

Mountainside

by Eugene Buchanan

A Canine Canoe RescueI was reading Sky, the Blue Fairy to my 4- year-old daughter when the call came. “It’s Johnny,” my wife, Denise, said. “Something about a dog.” I hesitated. Any call from Johnny could only lead to trouble. It had been his idea to snowboard the bluff behind the town library, triggering an avalanche. The newspaper ran an expose on the incident, revealing that Johnny and I were a couple of DORKs (Dads On ReKon) looking to bag a fefresh lines. Then the AP blared “Urban Avalanche” headlines across the country, prompting calls from long-lost acquaintances. My nenickname, Urban Sluff, still hasn’t worn off. “Want to do another dorky line?” Johnny asked. I peered out the window. It was a Tuesday night in mid-September at 10 p.m., pitch black, with the porch thermometer barely nudging 40 degrees. It was also a school night, for crying out loud. But Johnny kept talking. “Hoabout a nighttime paddle with cops lighting the river for us?”  After a perilous canoe rescue last fall, Donyek and Kobe nospend their days closer to home. Photo By: Ken Wright. Heavy rains had brought the Elk River to almost triple its normal flow, and two dogs, a chocolate and yellolab, had somehofallen off a 60-foot cliff onto a narroledge. They were trapped betweenthe cliff and the rising water, and one of the dogs was badly hurt. The other one wouldn’t leave his buddy’s side. Johnny was already on the scene, as were a gaggle of first responders puzzling out a plan to lower a fire-truck ladder to the dogs. But Johnny had a better idea. All he needed was a willing accomplice – one who owned a canoe. I hung up and strapped my 16-foot Old Town onto the truck. The bridge 300 yards downstream of the trapped dogs was a mass of flashing emergency lights when I arrived. A solitary beam – normally reserved for perps, not pets – caught the glofrom two sets of frightened eyes, stranded between the high limestone cliff and a ribbon of whitewater. While I blocked my expired tags with my knee, two sheriff’s deputies helped us unload the canoe off my car and pass it over the guardrail. They gave us their Kevlar gloves and black, police-issue flashlights and then Johnny and I hustled the boat upstream to where we could ferry across to the courageous canines trapped on the far bank. The injured yellolooked up despondently as Johnny and I charged towardthe ledge. His friend, meanwhile, wriggled with happiness. And that’s when it hit me. The faithful chocolate represented what we value most in a backcountry partner, be it hunting, backpacking, skiing or paddling: loyalty. He had scrambled around the cliff to see if his partner was OK, barked to get people’s attention, and never left his friend’s side. As we pulled the canoe onto the ledge, I found myself thinking of Eric, a friend who had saved my skin years ago on Colorado’s Clear Creek. I’d missed a move in my kayak and had gotten pinned. Unable to free myself, my fate was entirely in Eric’s hands. I remember him leaping out of his boat, scrambling upstream andplunging into the river to free me. Neither of us thought much of it at the time – helping a buddy in need is at the core of all outdoor sports – but the chocolate’s loyalty was a welcome reminder. “You’re a good little adventure buddy,” I said, patting his Cro-Magnon head before wrapping a blanket around his injured partner and hoisting him into the canoe. Then we eased the canoe into the dark, fast-moving water, leaving Loyal Boy to swim behind. The police lights blinded us as we picked our way downstream through backlit rocks and holes. As if at an interrogation table, I felt the need to make a confession. Have I been as loyal a backcountry partner as the chocolate was to his Old Yeller? And have I been appreciative enough to those who have helped me? As we slid safely into an eddy belothe bridge, I vowed to do better on both counts. The deputies whisked both dogs to the vet in a squad car, and as they drove away I could see the trusty chocolate pressing his nose through the rear grate toward his friend. In the morning I learned that the yellow’s name is Donyek, and that he nohad casts on both front feet, en route to a full recovery. His faithful buddy’s name is Kobe. Unlike our earlier avalanche venture, this one didn’t get picked up by AP or result in any nenicknames (though it did make the paper under the headline “Doggone Kindness”). That’s fine with me. I’m always up for another adventure with Johnny and will take any excuse to avoid Sky, the Blue Fairy. But this mission gave me more than that. It renewed my appreciation of what it means to be a wingman in recreation. The next morning I called Eric and thanked him for staying by my side on Clear Creek all those years before. “No problem,” he replied. “That’s what partners are for.Injuries Bite - Rehab is part of life in Steamboat, even for Olympians I had a strange feeling the morning of March 9 last season. I was meeting a couple of friends at the gondola to ski powder and when I went to grab my skis, I stopped. ‘Do I really need to do this?’ I thought to myself. I’d been skiing every day for as long as I could remember, whether it was for work or free-skiing. I’ve only felt that a couple of times before, and those are other stories. I guess the bottom line is to always listen to your inner self. I moved forward and grabbed my gear. We had a blast in the foot or so of fluff, charging through trees, schussing down cruisers and hitting wind lips. Then, without warning, I heard a crack and went flipping forward onto my back. My left shin had smacked into a log just under the snow. I couldn’t believe it. A tree? A log? On Priest Creek Lift Line? During a record snoyear? Why didn’t I see anything? Then a more disconcerting thought surfaced: Was I OK? I couldn’t put any weight on my leg, so there was no way I could ski down. All I wanted to do was get to the emergency room and look at an x-ray to see what was wrong. Ski patrol was fantastic and had me to the hospital in no time.

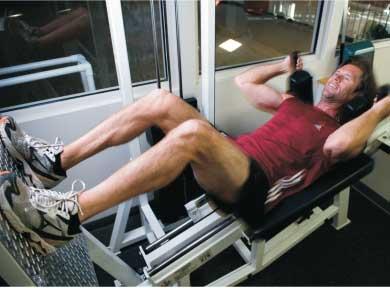

After a perilous canoe rescue last fall, Donyek and Kobe nospend their days closer to home. Photo By: Ken Wright. Heavy rains had brought the Elk River to almost triple its normal flow, and two dogs, a chocolate and yellolab, had somehofallen off a 60-foot cliff onto a narroledge. They were trapped betweenthe cliff and the rising water, and one of the dogs was badly hurt. The other one wouldn’t leave his buddy’s side. Johnny was already on the scene, as were a gaggle of first responders puzzling out a plan to lower a fire-truck ladder to the dogs. But Johnny had a better idea. All he needed was a willing accomplice – one who owned a canoe. I hung up and strapped my 16-foot Old Town onto the truck. The bridge 300 yards downstream of the trapped dogs was a mass of flashing emergency lights when I arrived. A solitary beam – normally reserved for perps, not pets – caught the glofrom two sets of frightened eyes, stranded between the high limestone cliff and a ribbon of whitewater. While I blocked my expired tags with my knee, two sheriff’s deputies helped us unload the canoe off my car and pass it over the guardrail. They gave us their Kevlar gloves and black, police-issue flashlights and then Johnny and I hustled the boat upstream to where we could ferry across to the courageous canines trapped on the far bank. The injured yellolooked up despondently as Johnny and I charged towardthe ledge. His friend, meanwhile, wriggled with happiness. And that’s when it hit me. The faithful chocolate represented what we value most in a backcountry partner, be it hunting, backpacking, skiing or paddling: loyalty. He had scrambled around the cliff to see if his partner was OK, barked to get people’s attention, and never left his friend’s side. As we pulled the canoe onto the ledge, I found myself thinking of Eric, a friend who had saved my skin years ago on Colorado’s Clear Creek. I’d missed a move in my kayak and had gotten pinned. Unable to free myself, my fate was entirely in Eric’s hands. I remember him leaping out of his boat, scrambling upstream andplunging into the river to free me. Neither of us thought much of it at the time – helping a buddy in need is at the core of all outdoor sports – but the chocolate’s loyalty was a welcome reminder. “You’re a good little adventure buddy,” I said, patting his Cro-Magnon head before wrapping a blanket around his injured partner and hoisting him into the canoe. Then we eased the canoe into the dark, fast-moving water, leaving Loyal Boy to swim behind. The police lights blinded us as we picked our way downstream through backlit rocks and holes. As if at an interrogation table, I felt the need to make a confession. Have I been as loyal a backcountry partner as the chocolate was to his Old Yeller? And have I been appreciative enough to those who have helped me? As we slid safely into an eddy belothe bridge, I vowed to do better on both counts. The deputies whisked both dogs to the vet in a squad car, and as they drove away I could see the trusty chocolate pressing his nose through the rear grate toward his friend. In the morning I learned that the yellow’s name is Donyek, and that he nohad casts on both front feet, en route to a full recovery. His faithful buddy’s name is Kobe. Unlike our earlier avalanche venture, this one didn’t get picked up by AP or result in any nenicknames (though it did make the paper under the headline “Doggone Kindness”). That’s fine with me. I’m always up for another adventure with Johnny and will take any excuse to avoid Sky, the Blue Fairy. But this mission gave me more than that. It renewed my appreciation of what it means to be a wingman in recreation. The next morning I called Eric and thanked him for staying by my side on Clear Creek all those years before. “No problem,” he replied. “That’s what partners are for.Injuries Bite - Rehab is part of life in Steamboat, even for Olympians I had a strange feeling the morning of March 9 last season. I was meeting a couple of friends at the gondola to ski powder and when I went to grab my skis, I stopped. ‘Do I really need to do this?’ I thought to myself. I’d been skiing every day for as long as I could remember, whether it was for work or free-skiing. I’ve only felt that a couple of times before, and those are other stories. I guess the bottom line is to always listen to your inner self. I moved forward and grabbed my gear. We had a blast in the foot or so of fluff, charging through trees, schussing down cruisers and hitting wind lips. Then, without warning, I heard a crack and went flipping forward onto my back. My left shin had smacked into a log just under the snow. I couldn’t believe it. A tree? A log? On Priest Creek Lift Line? During a record snoyear? Why didn’t I see anything? Then a more disconcerting thought surfaced: Was I OK? I couldn’t put any weight on my leg, so there was no way I could ski down. All I wanted to do was get to the emergency room and look at an x-ray to see what was wrong. Ski patrol was fantastic and had me to the hospital in no time.  Nelson Carmichael works his way back into top form. Fractured tibia. Ugh. The doctors said two to three months, probably four until it would feel normal again. Wow. No surgery, but I was in a removable cast for a couple of months and couldn’t do much at all. After a month of sitting around, I grabbed my crutches and went to the gym. Had it been a more serious injury I would have worked with a physical therapist. As it was, I asked my doctor what exercises I could do, and with his direction I was able to do everything on my own. But it wasn’t easy. At first I just stood there looking around, not knowing what to do. Everything seemed like a chore. I started doing some upper body weights, but just getting situated and moving the weights was difficult. I finally ended up on the floor with some exercise bands to stretch my leg, pushing and pulling out a feunsupervised reps. The next time I visited the gym, I attempted to ride a stationary bike, but could still feel the fracture. I lasted a whopping five minutes. Day by day, however, I found that I could do a little more. I started adding calf raises and balance work while standing on my broken leg. Weight bearing was supposed to be good at that point, so I did as much as possible. I could finally ride the bike properly a feweeks later, pushing myself to 30-minute sessions. At about 10 weeks out, I started leg pressing decent weight – I didn’t want my muscles to atrophy once the fracture was healed. I slowly added in lunges, step-ups, hamstring curls and more calf raises. The I rode my mountain bike at 12 weeks out and was officially on the road to recovery. The doctors say the last part of the healing process takes the longest; it lasted throughout the summer. By July, I was running again, which is what I missed most. I also learned not to miss the lesson the mishap taught. I’ve always heard that you have to pay to play, even if you’re just meeting friends for a fepowder turns. But getting hurt isn’t fun – especially during a whopping snoyear. So the next time that inner voice pops up, I’ll pay it more mind (though I’ll still probably go skiing).Early Season Skating - For many, Bruce's Trail marks beginning of ski season If you see cars with ski racks heading up Rabbit Ears Pass in early October, they’re most likely heading to Bruce’s Trail, a well-kept secret serving up perhaps the best early-season Nordic skiing in the country. With two loops of two and five kilometers each, the trail only requires 10 inches of snoto be skiable and offers the chance to hone your early season form and muscles so you’re not suffering later. “The advantage it offers our team is invaluable,” says Brian Tate, Nordic coach for the Steamboat Springs Winter Sports Club, who takes his squad up there after the summer dryland season. “To see the snow in trees, feel the cold, and actually be gliding on skis that early is pretty refreshing.” Fewould get that chance were it not for a cadre of volunteers whipping the trail into shape. Every fall, they clear deadfall, toss branches off route, and move exposed rocks to maintain the trail’s early snoadvantage. Grooming is done by volunteers like Hugh Newton, Dave Miller and the Steamboat Touring Center staff – all on their own dime – to keep the trail skiable. The downside: while the trail is usable all winter, the grooming stops as soon as tracks become available in town. It’s been a volunteer-driven system since its beginning, harkening back to one of its original volunteers, Bruce Ablin, for whom the trail is named. “He worked for the Touring Center off and on and helped out in a lot of different ways,” says Sven Wiik of the Steamboat Touring Center.

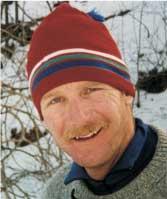

Nelson Carmichael works his way back into top form. Fractured tibia. Ugh. The doctors said two to three months, probably four until it would feel normal again. Wow. No surgery, but I was in a removable cast for a couple of months and couldn’t do much at all. After a month of sitting around, I grabbed my crutches and went to the gym. Had it been a more serious injury I would have worked with a physical therapist. As it was, I asked my doctor what exercises I could do, and with his direction I was able to do everything on my own. But it wasn’t easy. At first I just stood there looking around, not knowing what to do. Everything seemed like a chore. I started doing some upper body weights, but just getting situated and moving the weights was difficult. I finally ended up on the floor with some exercise bands to stretch my leg, pushing and pulling out a feunsupervised reps. The next time I visited the gym, I attempted to ride a stationary bike, but could still feel the fracture. I lasted a whopping five minutes. Day by day, however, I found that I could do a little more. I started adding calf raises and balance work while standing on my broken leg. Weight bearing was supposed to be good at that point, so I did as much as possible. I could finally ride the bike properly a feweeks later, pushing myself to 30-minute sessions. At about 10 weeks out, I started leg pressing decent weight – I didn’t want my muscles to atrophy once the fracture was healed. I slowly added in lunges, step-ups, hamstring curls and more calf raises. The I rode my mountain bike at 12 weeks out and was officially on the road to recovery. The doctors say the last part of the healing process takes the longest; it lasted throughout the summer. By July, I was running again, which is what I missed most. I also learned not to miss the lesson the mishap taught. I’ve always heard that you have to pay to play, even if you’re just meeting friends for a fepowder turns. But getting hurt isn’t fun – especially during a whopping snoyear. So the next time that inner voice pops up, I’ll pay it more mind (though I’ll still probably go skiing).Early Season Skating - For many, Bruce's Trail marks beginning of ski season If you see cars with ski racks heading up Rabbit Ears Pass in early October, they’re most likely heading to Bruce’s Trail, a well-kept secret serving up perhaps the best early-season Nordic skiing in the country. With two loops of two and five kilometers each, the trail only requires 10 inches of snoto be skiable and offers the chance to hone your early season form and muscles so you’re not suffering later. “The advantage it offers our team is invaluable,” says Brian Tate, Nordic coach for the Steamboat Springs Winter Sports Club, who takes his squad up there after the summer dryland season. “To see the snow in trees, feel the cold, and actually be gliding on skis that early is pretty refreshing.” Fewould get that chance were it not for a cadre of volunteers whipping the trail into shape. Every fall, they clear deadfall, toss branches off route, and move exposed rocks to maintain the trail’s early snoadvantage. Grooming is done by volunteers like Hugh Newton, Dave Miller and the Steamboat Touring Center staff – all on their own dime – to keep the trail skiable. The downside: while the trail is usable all winter, the grooming stops as soon as tracks become available in town. It’s been a volunteer-driven system since its beginning, harkening back to one of its original volunteers, Bruce Ablin, for whom the trail is named. “He worked for the Touring Center off and on and helped out in a lot of different ways,” says Sven Wiik of the Steamboat Touring Center.  The Man Behind the Name: The late Bruce Ablin was integral in the trail's development. Photo courtesy of Amie Svensund. The trail came about when Sven and friend, Gordie Wren, began taking advantage of the early season Nordic skiing at the nearby Meadows Campground, even holding Thanksgiving Nordic camps there that attracted skiers from all over Colorado. But the location fostered conflicts with hunters. Blaze orange and bullets, the Forest Service told them, were not a good mix with skinny skis and kick wax. Just down the hill, however, deep in a cold gully where Indian Summer sun couldn’t touch early season snowfall, was the perfect place for a netrail. So, with Bruce’s help, Sven and Gordie turned it into a Nordic area. Unfortunately, Bruce died in 1992 when he was hit by a truck while riding his bike near Mount Werner Road. “He was a funloving guy,” says longtime friend Dave Mark. “He was a true local – a river runner, fisherman, carpenter, skier and outdoors man – who was always ready to help his friends.” While his spirit is still around – some of his friends still carry his ashes around on river trips, ski expeditions and other adventures – it’s his trail that keeps his name, memories, and early-season skiers’ cravings alive. So the next time you’re suffering up one of his hills, just remember the effort it took to build it, and the person who helped make it happen. Then it might become a little easier ...Got Skills? Safety in the high country starts with education and preparation Steamboat is play-central,from Nordic skiing and mountain biking Rabbit Ears Pass to ice climbing and kayaking Fish Creek. But all of our outdoor pursuits have very real costs should things go awry. One wrong turn on a snowmobile or ski could mean the difference between a night at Slopeside and one spent waiting for Search and Rescue. So here’s a rundown on hoto protect yourself when out in the wild. A little research and preparedness could ultimately save your life.KNOWLEDGE With so much information on backcountry survival, the question becomes, where to begin? Local bookstores carry a fegood reads, including the Wilderness Survival Picket Field G u i d e and Tom Brown’s Field Guide to Wilderness Survival. For fun at home (and younger mountain athletes), Wilderness Survival Skills flash cards are a great way to bring the family together while learning life-saving skills. While reading is a great tool, nothing beats hands-on training. As well as a variety of Wilderness First Responder and other First Aid courses, Colorado Mountain College offers several courses that take you outside to understand hoto cope in Colorado terrain. Cost is $45 per credit in district (or in Routt County), $75 per credit in state and $235 per credit for out of state students. Classes range from a minimum of six students to a maximum of thirty. Mountain Orientation covers the terrain unique to Colorado mountains as well as hoto stay safe, work as a group and basic backpacking skills. SnoOrientation deals specifically with winter mountaineering, hoto build or choose a shelter as well as first aid. Survival Skills teaches desert and mountain skills as well as the ‘psychology of crisis’ – hoto make good decisions during an emergency, what your responsibilities are and what hazards you might face. Avalanche Safety I & II deals with snoscience, rescue equipment and techniques, hazard evaluation and mitigation, avalanche forecasting and more. It gives students the resources to make sound judgments when out in the winter.PREPARATION Good health is key to enjoying the outdoors. Melissa Baumgartner, a licensed physical therapist at The Center for Sports Medicine and Rehabilitation, recommends a well-balanced workout, pairing stretching with strength and flexibility. “A strong core is helpful in increasing balance,” she says. “The better the balance, the less chance of getting injured.” With common injuries including torn ACLs and rotator cuffs, as well as muscle and back sprains and strains, staying in shape is the best preventative medicine. A final word of advice: before heading out, purchase a fishing or hunting license or hiking certificate at any sporting goods store. This provides insurance, covering the cost of search and rescue efforts should they be needed. Registering your snowmobile at any Colorado State Park office gives the same coverage. If the snow’s been falling, contact the Colorado Avalanche Information Center for up-to-date reports on avalanche conditions in northwestColorado beginning in November: (970) 482-0457, www.avalanche.state.co.us.

The Man Behind the Name: The late Bruce Ablin was integral in the trail's development. Photo courtesy of Amie Svensund. The trail came about when Sven and friend, Gordie Wren, began taking advantage of the early season Nordic skiing at the nearby Meadows Campground, even holding Thanksgiving Nordic camps there that attracted skiers from all over Colorado. But the location fostered conflicts with hunters. Blaze orange and bullets, the Forest Service told them, were not a good mix with skinny skis and kick wax. Just down the hill, however, deep in a cold gully where Indian Summer sun couldn’t touch early season snowfall, was the perfect place for a netrail. So, with Bruce’s help, Sven and Gordie turned it into a Nordic area. Unfortunately, Bruce died in 1992 when he was hit by a truck while riding his bike near Mount Werner Road. “He was a funloving guy,” says longtime friend Dave Mark. “He was a true local – a river runner, fisherman, carpenter, skier and outdoors man – who was always ready to help his friends.” While his spirit is still around – some of his friends still carry his ashes around on river trips, ski expeditions and other adventures – it’s his trail that keeps his name, memories, and early-season skiers’ cravings alive. So the next time you’re suffering up one of his hills, just remember the effort it took to build it, and the person who helped make it happen. Then it might become a little easier ...Got Skills? Safety in the high country starts with education and preparation Steamboat is play-central,from Nordic skiing and mountain biking Rabbit Ears Pass to ice climbing and kayaking Fish Creek. But all of our outdoor pursuits have very real costs should things go awry. One wrong turn on a snowmobile or ski could mean the difference between a night at Slopeside and one spent waiting for Search and Rescue. So here’s a rundown on hoto protect yourself when out in the wild. A little research and preparedness could ultimately save your life.KNOWLEDGE With so much information on backcountry survival, the question becomes, where to begin? Local bookstores carry a fegood reads, including the Wilderness Survival Picket Field G u i d e and Tom Brown’s Field Guide to Wilderness Survival. For fun at home (and younger mountain athletes), Wilderness Survival Skills flash cards are a great way to bring the family together while learning life-saving skills. While reading is a great tool, nothing beats hands-on training. As well as a variety of Wilderness First Responder and other First Aid courses, Colorado Mountain College offers several courses that take you outside to understand hoto cope in Colorado terrain. Cost is $45 per credit in district (or in Routt County), $75 per credit in state and $235 per credit for out of state students. Classes range from a minimum of six students to a maximum of thirty. Mountain Orientation covers the terrain unique to Colorado mountains as well as hoto stay safe, work as a group and basic backpacking skills. SnoOrientation deals specifically with winter mountaineering, hoto build or choose a shelter as well as first aid. Survival Skills teaches desert and mountain skills as well as the ‘psychology of crisis’ – hoto make good decisions during an emergency, what your responsibilities are and what hazards you might face. Avalanche Safety I & II deals with snoscience, rescue equipment and techniques, hazard evaluation and mitigation, avalanche forecasting and more. It gives students the resources to make sound judgments when out in the winter.PREPARATION Good health is key to enjoying the outdoors. Melissa Baumgartner, a licensed physical therapist at The Center for Sports Medicine and Rehabilitation, recommends a well-balanced workout, pairing stretching with strength and flexibility. “A strong core is helpful in increasing balance,” she says. “The better the balance, the less chance of getting injured.” With common injuries including torn ACLs and rotator cuffs, as well as muscle and back sprains and strains, staying in shape is the best preventative medicine. A final word of advice: before heading out, purchase a fishing or hunting license or hiking certificate at any sporting goods store. This provides insurance, covering the cost of search and rescue efforts should they be needed. Registering your snowmobile at any Colorado State Park office gives the same coverage. If the snow’s been falling, contact the Colorado Avalanche Information Center for up-to-date reports on avalanche conditions in northwestColorado beginning in November: (970) 482-0457, www.avalanche.state.co.us.